Concordia Seminary Newsroom

Pursuing Patristic Exegesis

Meet: Dr. David Maxwell

by Sarah Maney

For well over 1,500 years the early church fathers interpreted the Bible differently than we do today.

“Yet, we don’t talk much about it,” says Dr. David Maxwell, the Louis A. Fincke and Anna B. Shine Professor of Systematic Theology and the new chairman of Concordia Seminary’s Department of Systematic Theology.

Maxwell calls this an “exegetical elephant in the room,” one that prompted his foray into patristic exegesis, which is the study of how the early church fathers interpreted the Bible.

“Learning about the early church helps us — laypeople and clergy — figure out our place in the broader Christian tradition,” Maxwell says.

Maxwell initially became interested in the field of the early church primarily “because in Lutheranism, you have the Reformation, which talks about how we need to sharpen the church’s view of justification by faith. But that suggests that there’s some kind of discontinuity between us and the church before the Reformation,” Maxwell says. “On the other hand, if you look at the Book of Concord, you will see, in a number of places, that we’re in continuity with the early church. And so, I wondered, ‘Which is it?’”

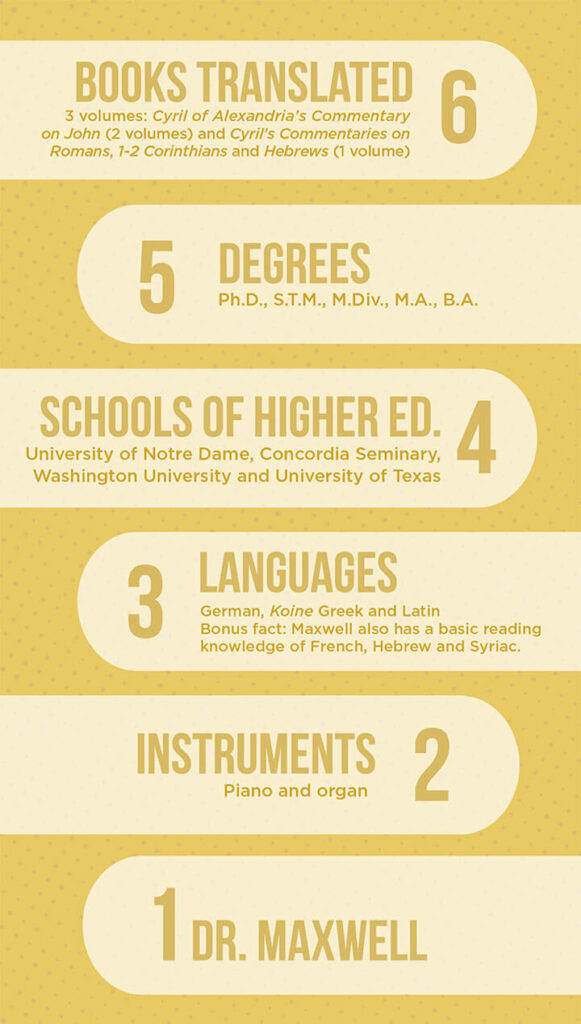

This compelled Maxwell to deeper study, eventually obtaining a Ph.D. in this area from the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Ind., in 2003.

Maxwell joined the Concordia Seminary faculty in 2004. As he was translating Cyril of Alexandria’s Commentary on John (InterVarsity Press), Maxwell wondered how the early church read the Bible? Not just what they say about justification, but their approach to the biblical text in general?

“Cyril is a church father who lived in the fourth and fifth century. And so, I researched in depth what he did with the biblical text. And it dawned on me that this is not exactly what we do with the biblical text. And so that’s an interesting difference.”

In the early church, the meaning of a certain Scripture text was found in its role in the larger story of salvation, while in contemporary exegesis, the meaning of the text is found in the original intent of the author as it was understood by the original readers in the historical context.

In addition to Cyril of Alexandria’s Commentary on John, Maxwell also translated Cyril of Alexandria’s Commentaries on Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, and Hebrews (InterVarsity Press). This translation work led to an interest in teaching students not only to read Koine Greek but also to listen to and speak the language. Maxwell leads an online group in listening and speaking Koine Greek. People from all over the country participate.

Learning to speak the language gives a “more intuitive sense of the language,” Maxwell says. “You learn it on a deeper level. If you experience it, not only trying to read it and parse the verb forms, but actually think in it and speak it and even dream in it, you just know it better.”

It was his study of Latin and Greek in college that played a role in discerning whether to go into the ministry. He also credits his grandfather with encouraging him to enter the ministry, a decision Maxwell made halfway through college.

After receiving his undergraduate degree from the University of Texas at Austin, he went on to study for not one, but two master’s degrees — a Master of Divinity (M.Div.) at Concordia Seminary and a Master of Arts (M.A.) from Washington University, St. Louis — graduating from both in 1995.

“It was a lot of work,” Maxwell says. “At Washington University, I read a lot of Greek and Latin for my classes, and it made me better at those languages.”

Maxwell obtained a Master of Sacred Theology from Concordia Seminary in 1997.

Maxwell notes that Greek often is viewed as instrumental in a seminarian’s studies since the New Testament originally was written in Greek. But understanding Latin also is extremely important for understanding the history of the church, he said.

“Latin was used all the way through the Reformation. The 95 Theses were written in Latin. Half of Luther’s writings more or less were in Latin, not German, because that was the language for academic or scholarly work in the Middle Ages so that anyone could read them in other countries,” explains Maxwell, who teaches Latin in addition to courses in systematic theology, patristics and the history of exegesis.

Not only is Maxwell a theologian, he also is a musician. He became interested in playing the organ after growing up in the church and loving the hymns the organist played.

“I especially like Bach and the baroque period, and that’s kind of the heart and soul of organ music to begin with. So, it just seemed natural to love this music, and I decided I was going to learn how to play it,” Maxwell says.

Maxwell studied organ in college. “I was not a music major. This was just an elective. But the organ professor made me promise that I would practice 10 hours a week. That was the condition for me to take the organ and I did it. I was amazed at how much progress you can make if you actually practice for 10 hours a week,” he says.

Today he plays the organ regularly in church and at the Seminary. In conjunction with playing the organ, he has written on the theological symbolism in the organ music of J.S. Bach, particularly Bach’s “Clavierübung III,” which is based on Luther’s catechism hymns. More recently, he has produced organ videos on this topic, which are available at concordiatheology.org.

Maxwell certainly is a gifted theologian, linguist and musician. But most importantly, he does not keep his research or acquired knowledge and skill to himself. Whether he is teaching at the Seminary, leading his Koine Greek group, speaking at a symposium or Lay Bible Institute, translating commentaries or playing the organ for his church — Maxwell shares the good gifts that God has given him with others so that he might glorify God and help build others up in the faith.

Sarah Maney is a communications specialist at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis.